Problem Tree Analysis

From Learning and training wiki

| Problem Tree Analysis is a tool that helps to identify the negative aspects of an existing situation and establish the “cause and effect” relationships between the identified problems.[1] |

Why to use it?[2]

- The problem can be broken down into manageable and definable chunks. This enables a clearer prioritization of factors and helps focus objectives;

- There is more understanding of the problem and its often interconnected and even contradictory causes. This is often the first step in finding win-win solutions;

- It identifies the constituent issues and arguments, and can help establish who and what the political actors and processes are at each stage;

- It can help establish whether further information, evidence or resources are needed to make a strong case, or build a convincing solution;

- Present issues – rather than apparent, future or past issues – are dealt with and identified;

- The process of analysis often helps build a shared sense of understanding, purpose and action.

Step By Step[3]The problem tree should be developed as a participatory group activity. 6 to 8 people is often a good group size. It is important to ensure that groups are structured in ways that enable particular viewpoints, especially those of the less powerful, to be expressed.[4]

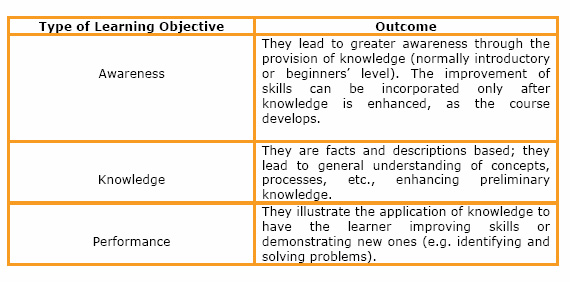

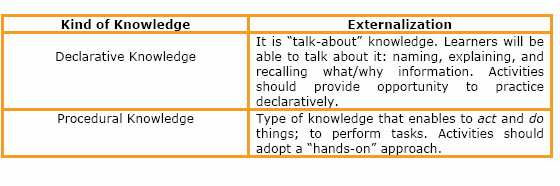

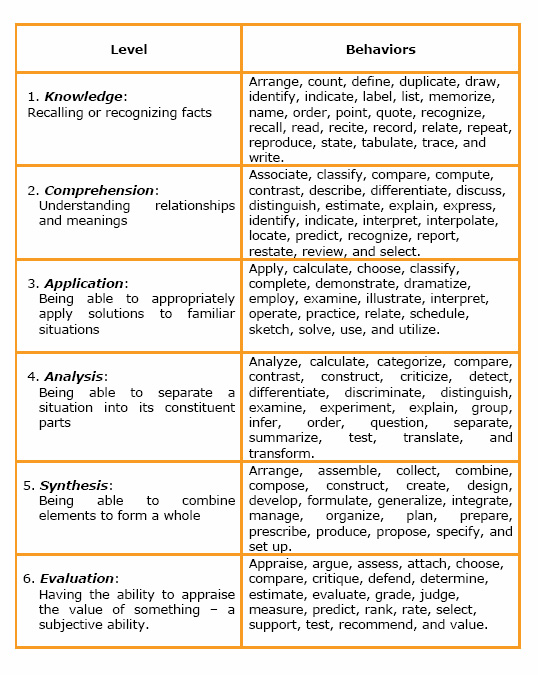

The heart of the exercise is the discussion, debate and dialogue that is generated as factors are arranged and re-arranged, often forming sub-dividing roots and branches.[5] Identify the kind of knowledge learners will acquire:

Quick CheckWhen writing learning objective statements, ask yourself the following questions:

Job Aids

|

| The following documents contain examples of learning goals and objectives developed according to the instructions: |

| General learning goals and objectives developed for different courses outside UNITAR. | |

| Learning objectives developed for UNITAR course on Urban Sanitation. | |

| Learning objectives developed for UNITAR / UNDP course on Democratic Governance. |

References

- ↑ European Commission, « Aid Delivery Methods : Volume 1 Project Cycle Management Guidelines », March 2004.

- ↑ [1](22 October, 2009).

- ↑ European Commission, « Aid Delivery Methods : Volume 1 Project Cycle Management Guidelines », March 2004, and NZAID Tools, “Logical Framework Approach”, http://nzaidtools.nzaid.govt.nz/logical-framework-approach/annex-2-problem-tree-analysis (22 October, 2009)

- ↑ NZAID Tools, “Logical Framework Approach”, http://nzaidtools.nzaid.govt.nz/logical-framework-approach/annex-2-problem-tree-analysis (22 October, 2009)

- ↑ Overseas Development Institute (ODI), http://www.odi.org.uk/RAPID/Tools/Toolkits/Communication/Problem_tree.html (22 October, 2009)

- ↑ Hassel-Corbiell, Ribes, Developing Training Courses: a technical writer’s guide to instructional design and development, Learning Edge Publishing, 2006.