Difference between revisions of "Gamification of Learning Processes"

From Learning and training wiki

| Line 79: | Line 79: | ||

{{Addlink|}} | {{Addlink|}} | ||

| + | {|border=1 | ||

| + | !width= 200pt|Link | ||

| + | !width= 575pt|Content | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{Addmaterial|}} | ||

| + | {|border=1; width= 100% | ||

| + | !width= 200pt|Document | ||

| + | !width= 575pt|Content | ||

| + | |} | ||

== References == | == References == | ||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

Revision as of 14:36, 11 November 2013

{{Term|GAMIFICATION OF LEARNING PROCESSES|Gamification of learning processes can be understood as the use of game design elements in learning environments in order to enhance the level of engagement of the learner. As explained in the respective article, the most generally adopted definition for gamification is: “gamification is the use of game design elements (such as badges, points and leaderboards) in non-game contexts”[1]. For an increased level of engagement, an increased level of motivation is required and games elements such as badges, points and leaderboards may be powerful motivational agents when applied in a meaningful way. All these elements (taken from games) concern extrinsic motivation, which “refers to behavior that is driven by external rewards such as money, fame, grades, and praise. This type of motivation arises from outside the individual, as opposed to intrinsic motivation, which originates inside of the individual.”[2] Being so, it has been intensively discussed that extrinsic motivational strategies have a finite term, meaning that their effectiveness may not last. This phenomenon is called replacement or over justification:

“The over-justification effect occurs when an expected external incentive (reward) such as money or prizes decreases a person's intrinsic motivation to perform a task. According to self-perception theory people pay more attention to the external reward for an activity than to the inherent enjoyment and satisfaction received from the activity itself. The overall effect of offering a reward for a previously unrewarded activity is a shift to extrinsic motivation and the undermining of pre-existing intrinsic motivation. Once rewards are no longer offered, interest in the activity is lost; prior intrinsic motivation does not return, and extrinsic rewards must be continuously offered as motivation to sustain the activity.”[3]

Check this article where Gabe Zichermann`s (the most prominent pro-gamification guru) responds to this line of criticism.

The first gamified environment

The learning environment was the first one to be gamified (from school grades to boyscouts` badges). This fact brings some topics for reflection:

Degamifying

Today many approaches focus on degamifiying learning environments, by criticizing the way people are submitted to tests, which fail to assess the real potential of the learner.

Overgamification or regamification?

Others are seeking to gamify learning environments; however, we have learned that it is already a gamified system. So we are not talking about gamifying but about overgamifying or regamifying. To overgamify may be understood as being redundant, for instance by adding points to something that is already based on grades or give badges for something that already provides a certificate. To regamify may be understood as deconstructing and reconstructing the system, by letting the old aside and implementing innovative strategies, even if armored with the same principles. As an example of [over- or re-] gamification (it will be up to you to conclude), one may take a look at the use of platforms, such as Class Dojo, which are exploring the power of the virtual world by creating avatars (representation of the persona in this virtual world) for each learner, and the avatars get the rewards (it may be a skill through badges, a title such as Dr. or Prof., a new jacket or a hair style) for achievements of the “real” learner. It turns out that it is effective. But what makes it so effective, if it is using the same old reward systems, just dressed up in a different way? What is the difference between the old reward and the digital, visual reward? Three theories follow:

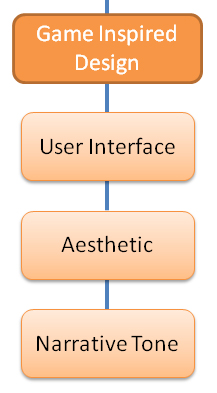

1. Game Inspired Design

As defined by Andrzej Marczewski:

“This used to be called gameful design, but this now has more gamification like connotations. This is where no actual elements from games are used, just ideas. So user interfaces that mimic those from games, design or artwork that is inspired by games or the way things are written. All of these have links to games, but do not contain anything that you would consider to be part of a game (mechancics, dynamics, tokens etc.)” [4]

The visual appeal of games is ludic, what makes people more willing to interact with it. Through user interface, aesthetic and the use of the right narrative tone, it is possible to turn some boring website or even a text (or a course) into something that resembles the aesthetic of video-games, borrowing from it its ludic appeal, its playfulness and therefore motivating users/learners to interact.

One may think like this: if your reward after succeeding in a test does not look like a “10” or an “A”, but it is a beautiful designed badge, which will be attached to your “hype” avatar, who may even get the possibility to buy new shoes as a reward of your efforts. That is game inspired design.

2. The performance exposure – embracing competition

One`s score/grade used to be private, teachers used to give the results personally without announcing it to the whole class, to avoid public shame (in the case of those who did not perform so well). Now with [over- or re-] gamification (or pointsfication) the points of the avatar and its achievements are public, anyone can see (in the case of explicit exposure). And if the points are not public, just those who did “well” will have a nice badge (which are per definition public), and those who do not have a badge had obviously a “not good enough” performance to earn one, which is an implicit exposure.

Before [over- or re-] gamification, learners used to ask their colleagues “hey, what was your grade in the math test?”, which reflects the human innate inclination for competition[5], and there was choice of revealing it or not. As we have seen, in [over- or re-] gamified processes, this choice is (in most cases) no longer available. The use of leaderboards is also a common practice in [over- or re-] gamification, which is the highest sign of a system that embraces competition as a way of improving performance.

3. Both - theories numbers one and two resemble the pleasure of playful activities, in which learners take part in during their free time, therefore the combination of both turn out to be effective.

After attending a [over- or re-] gamified class, when given the choice for the format of upcoming classes, the majority of interviewed learners would go for the [over- or re-] gamified class once more, stating that it is “less boring” (but they also do not say that it is fun, because it is not a game in its full sense). This shows that either the competitive environment or the game inspired design is highly appreciated by learners, or both as a combination.

Overlapping terms

It is impressive to see how many people are still talking and writing mistakenly about game-based learning (learning games, serious games) and naming it gamification of education, - of the classroom, - of learning and training. The distinction between these terms is paramount: gamification regards the application of some selected game elements (points, badges, leaderboards) into non-gaming contexts, acting as extrinsic motivational tools. Many game theorists and game designers claim that “gamification” misuses the word “game” by referring to techniques that exclude the most relevant elements of game design and game thinking, suggesting “pointsification” as a better suiting label for the practice. Thus by excluding the most relevant elements of games (those which turn the activity from a ordinary one into a ludic one, providing a full game experience), such as narrative, immersion, music, visuals and addictiveness, gamified activities or practices should not be named “games”.

Serious games and learning games provide a full game experience, differentiating themselves from gamified activities/practices. Serious games and learning games are the platform for the application of game-based learning approaches, which should be a better alternative than gamification when concerned to learning environments. Summing up, the gamification of learning processes is about bringing simple elements from games into learning environments, whereas game-based learning will bring the learning content and activities into the game, becoming then the learning environment itself. However the gamification of content and environments is more simple and therefore faster and cheaper than the creation of a game, wherein the learning process will take place. And this is the reason why so many people have been choosing the cheap and fastest way, which may in its turn be loaded with several moral issues, to be discussed bellow.

In addition you may follow the links below, which relate to articles distinguishing gamification of learning processes of game-based learning:

Gamification vs. Game-based learning in education

Game-based learning vs. gamification

Game-based learning, gamification, game

| Link | Content |

|---|

| Document | Content |

|---|

References

- ↑ Deterding et al. From Game Design Elements to Gamefulness: Defining “Gamification”. 9-15. p.10.

- ↑ http://psychology.about.com/od/eindex/f/extrinsic-motivation.htm

- ↑ Carlson, R.Neil and Heth, C. Donald (2007).Psychology of the Science of Behaviour. Pearson Education: New Jersey.

- ↑ Andrzej Marczewski in: http://marczewski.me.uk/2013/10/21/game-thinking-breaking/

- ↑ Watch this video: do we play games?